- By Dan Veaner

- Around Town

Print

Print  November 10th is the 239th Marine Corps Anniversary, just a day before Veterans Day. The Marine Corps has a proud tradition. Any Marine will tell you there are no ex-Marines. In 1944 Ithaca High School graduate Robert Boda joined and in 1945 he found himself in the Fifth Marine Regiment, First Marine Division, Second Battalion, Fox Company on the front lines in the thick of the Battle of Okinawa, the last major battle before the bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

November 10th is the 239th Marine Corps Anniversary, just a day before Veterans Day. The Marine Corps has a proud tradition. Any Marine will tell you there are no ex-Marines. In 1944 Ithaca High School graduate Robert Boda joined and in 1945 he found himself in the Fifth Marine Regiment, First Marine Division, Second Battalion, Fox Company on the front lines in the thick of the Battle of Okinawa, the last major battle before the bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki."Eighty eight percent of the 55th Replacement Draft got killed," says Boda. "I'm one of the twenty percent that came back home."

Boda wanted to be a Marine from the beginning. After high school Boda's football coach hooked him up with a friend who was a Marine recruiter. Boda says he liked the Marines best of all the armed services, and that's where he wanted to serve.

"I suppose it was because of watching these movies," he says. "I always did like the Marines."

Two weeks before Christmas Boda went to Syracuse for a medical examination, then immediately found himself in Buffalo, where he was sworn in and transported to boot camp at the Marine Corps Recruit Depot Parris Island in Port Royal, South Carolina.

"I spent my first Christmas ever away from home on Paris Island," Boda says. "We went through our training there and got a ten day leave to go home. Then I had to report back to Paris Island. We were supposed to have extended training before relieving fighters on the front line, because they lost more soldiers in Okinawa than any other battle."

Boda's group was rushed into the 55th Replacements Draft at Camp Lejeune. They were given three days of advanced training, then were sent off to war.

"They put us on board a ship and that night President Roosevelt died," he recalls. We had to stay in Norfolk Harbor until noon that day, with all the flags at half mast. We left Norfolk in a troop transit ship and went down to the Panama Canal. On the other side, going out into the Pacific we saw our first sign of a battle with the Japanese."

The USS Franklin ('Big Ben') returns to Pearl harbor after being bombed by the Japanese. From the Photograph Collection Marine Corps Archives & Special Collections

The USS Franklin ('Big Ben') returns to Pearl harbor after being bombed by the Japanese. From the Photograph Collection Marine Corps Archives & Special CollectionsWhat he saw was the devastated aircraft carrier USS Franklin, limping home after a vicious attack by the Japanese. Bombs had hit the ammunition locker filled with rockets and shells, killing sailers on the flight deck and the hangar deck. Somehow the ship made it home, but 724 sailors died and another 165 were wounded.

"The kamikazes bombed it. It must have gotten so hot that the guns were bent right over. There were two submarines escorting it -- they wanted to save the aircraft carrier. It was quite a sight!"

Next stop: Pearl Harbor.

"When I got to Pearl Harbor the Arizona was still sunk," he remembers. "They hadn't started taking it apart yet. We were there four weeks. The seventh fleet was getting ready for the 'Big Bang', because Okinawa was the last step before they hit Japan."

Boda found himself in a convoy headed toward Okinawa. The north of the island was secured, so the plan was to fight down to the south. The Japanese strategy was to let the Americans in, then surround them and attack.

"But our officers were smarter," Boda says. "Instead of them pinchering us, we pinchered them. Japan wanted to to that to us, but instead we separated them."

"While I was there our general got killed. Toward the end of the battle they had a big movement. He wanted to see how the soldiers were fighting, so he went to an outlook. Somehow the Japanese knew he was there. An artillery shell hit the coral and a piece about a foot wide hit him in the chest. When a general goes you've got to replace him!"

"They were sending us to the front lines at Shuri Castle," he recalls. "We were loaded in the back of a weapons carrier. They opened up on us when we got to the river that goes into Naha on the bay. We hadn't even reached the line yet."

Boda says troops his unit was replacing were on the front line so long they needed to be replaced.

"So we're sending a bunch of guys with three days advanced training. When the Lieutenant gave you your sign you passed it on to your men. Well some of them didn't know the signs. I knew my signs because I was working for corporals."

That may have saved his life. Hand signals, or signs, were used to tell soldiers what to do -- get up, stay down, move to a location, and so on. Because the island was made of so much coral the places to dig in were shallow. If you poked your head up at the wrong time, chances were good that a Japanese bullet would find you.

Raising the American Flag after the capture of Suri Castle - From the Photograph Collection, Marine Corps Archives & Special CollectionsFor fourteen days Boda's group secured one area, then was pulled down to secure another area. After Suri Castle had been secured he was moved to Hill 81, which they thought was an ammunition storage area. It was hard to tell, because the Japanese were dug into caves. It turned out to be a hospital.

Raising the American Flag after the capture of Suri Castle - From the Photograph Collection, Marine Corps Archives & Special CollectionsFor fourteen days Boda's group secured one area, then was pulled down to secure another area. After Suri Castle had been secured he was moved to Hill 81, which they thought was an ammunition storage area. It was hard to tell, because the Japanese were dug into caves. It turned out to be a hospital."They wanted that bad," he says. "We lost a lot of men there. I was on the phone at the time, calling for light flares. They told me to go back in. When they asked you to do a job, you did the job."

Boda recalls that the Japanese rifles used 31 caliber ammunition, but the American guns used 30 caliber. That meant the Japanese could steal American ammunition, but Japanese ammunition did not fit in American rifles. That meant the Japanese would forage the battlefield to replenish their depleted ammunition.

"That night they got 25 Japanese soldiers trying to get out because they needed water, food, and ammunition, he says. "The closest to me was about ten yards. i was in a little hole. Not much because you couldn't dig there. You got behind coral or a tree or something. I was lucky. Very lucky. I came close to it and saw a lot of my buddies go down. You don't realize what goes through your mind when you're up there on the front line. It's a lot different from back home."

Boda remained there through the end of the battle. Okinawa was secured by American troops, but a treaty had yet to be signed.

"One day a big white airplane with a big red cross came into the airfield with high Japanese officials to sign the surrender for the island," he says. "But you know the big surrender was up in Tokyo Bay where the seventh fleet was. I was on Okinawa when they dropped the two bombs. That ended the war right there."

Today people believe that using nuclear weapons is wrong. But in 1945 Truman saw the bombs as a way to end the war quickly, saving both American and Japanese lives.

"People often ask me how I would fight one of these wars over again," he reflects. "We're in Syria right now and being a little 'smart' I say, 'Oh I'd drop a bomb.' They say 'Oh you can't do that.' I say, 'Why? Turman said OK and that ended the war. We got a lot of people but we didn't have any more casualties and fighting. And they surrendered.'

"We were training and getting ready to go when they dropped the bombs. How happy we were -- we found out our company was scheduled to hit Tokyo Bay. Can you imagine what that would have been like? But they didn't want to take the chance. They had lost too many people."

After the Japanese surrendered the Fifth Marines were reassigned to guard coal mines in China. Chiang Kai-shek had received millions of American dollars to upgrade his coal mines. Boda says he took the millions, but never paid back the money, so the United States considered the mines US property. Eventually the Russians came through Manchuria, and the Americans left. While serving in China he was promoted to Corporal.

When Boda was done in China he could have stayed in the Marines, and would likely have been sent to Korea. But he wanted to go home. He left the service on October 26th, 1946. He moved back to Ithaca to embark on a career as a cabinet maker at Robinson Carpenters in Ithaca. He married his school sweetheart Ina in 1949. In 1965 he got a job at the Lansing Girls School as head carpenter. By the time Boda retired in 1988 he had been promoted to Maintenance Supervisor. The Bodas have two sons, a daughter and six grandchildren.

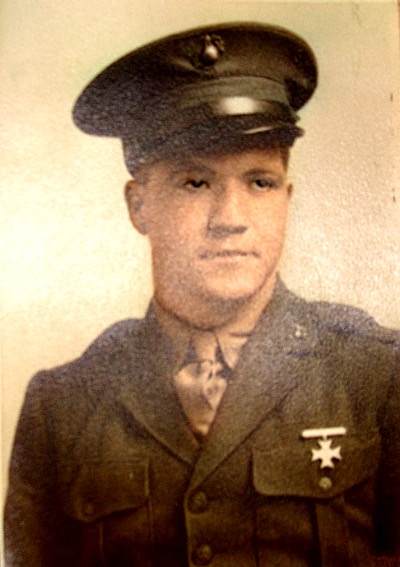

Bob Boda in 1946

Bob Boda in 1946 Bob Boda in his Lansing home today

Bob Boda in his Lansing home todayToday he and Ina live in Lansing. At 88 years old he is fighting cancer, and says he set a goal of lasting long enough to see all his grandchildren graduate from college. He'll reach that goal next fall when the youngest receives her nursing degree from TC3. Recently he told his doctor he'd like to hang on until he's 92, and he's optimistic he will reach that goal as well.

"If you have a good attitude and live well you'll make it," he says.

On November 10, 1775 the United States Marine Corps was formed by an Act of Congress. It directed that two battalions of Marines be raised for service on land and sea'. Those battalions, equaling 1,200 men, had their roots in the Continental Marines, which were disbanded in April 1783 after the Revolutionary War. Through the years they have continued to play a vital role in American history. Since Boda served they have been part of the Korean War, Vietnam War, and the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. On Monday Marines will celebrate their anniversary at Marine posts all over the world.

Boda plans a quiet remembrance at home. Unlike many World War II veterans who keep their experiences bottled up, Boda says the story should be told. People should know about the sacrifices young men made for their country. He is proud of his service.

"I was lucky," Boda says. "I would't want to do it again. But I'm glad I did it."

v10i42